Oct 28, 2025 This is the fifth and final in our 2025 Haunted Heritage blog series. See all the entries in the series here. What happens to the ghosts in a ghost town? Or to the spirits of a heritage building that is demolished, or burns down? This past winter, the hotel in my hometown burned to the ground, releasing many ghosts into the community and bringing up some for me personally. For six years, I conducted a haunted history tour (2012-2018) and I spent hours in that hotel sharing the many ghost stories associated with it. With the building now gone, my mind drifted back to that question - what happens to the ghosts? It was a question I posed to tour participants, not knowing at the time that it was a bit prescient. Some of the stories on the tour were about the supposed ghosts that haunted a house in a nearby village that no longer exists. Ghosts are so often associated with a specific place that imagining them divorced from place is hard to do. Soon enough, I had to reckon with this on the tour itself, which was built around the two most notoriously haunted sites in town - the hospital and the hotel. About three years after the tour started, the hospital was demolished. Some folks assumed the tour could not continue without this building, but it did because the stories were compelling enough to stand on their own, even with the building gone. In fact, I think that continuing to tell these stories helped some community members grieve this building that so many of them had been born in, sat with loved ones in their final days, and spent countless hours working. The tour did not suffer because the building was gone. In fact, it was wildly popular throughout its tenure because people love ghosts. As the tour grew a life of its own, I developed a bit of a pitch - people come for the ghosts, but they stay for the history. And it’s true that haunted history sells, especially at this time of year, and heritage practitioners are often called on, as in this blog series. Of course, one could argue that ghost stories are just entertainment, a bit of fun. People like to be scared silly, especially around Halloween, and ghost stories have the goods. However, I do not think that argument adequately acknowledges the role of history. To understand a ghost story requires some context. And this is why heritage practitioners are summoned this time of year to speak about ghosts - they necessarily contain the past. A ghost, as is commonly understood, is someone who once lived, in the past. And, like all heritage, it can only be understood and interpreted in the present and therefore is informed by our assumptions, values, and knowledge. When we tell each other ghost stories, we are saying something about what’s important to us now. And part of why ghost stories are so enduring is because they get to the very heart of preoccupations that humans have always had: mortality, connection to home/place, identity, and belonging. The idea of a ghost presupposes the fact of a person - someone who lived and experienced the human emotions, trials, tragedies and triumphs that we all do, on whatever scale and trajectory we live our lives. This is perhaps why hauntings are so compelling to us, and how effective ghost stories are at connecting people with the past. It helps us feel interested in a place and its past when we can picture people living, working, interacting within the same spaces that we now inhabit. By now I have been told and have retold hundreds of stories of ghosts, the supernatural, and other than human experiences through my work as a heritage practitioner. At first, I went looking for them. In his post introducing the series, David posed the question, “As far as research is concerned, there are a number of ethical questions this situation might raise, like who owns local history?” When I was creating the haunted history tour, I solicited ghost stories, and perhaps because I was still in university and was having research ethics drilled into me, I was really concerned with protecting the anonymity of informants. When I led the tour it was with the caveat that all the stories were told to me personally but that I would not reveal my sources. As the tour went on, some people were willing, even eager, to “out” themselves as the sources of certain stories - upstanding members of the community “owning” their experiences, so to speak, lent a certain legitimacy to the tour overall. And the promise of anonymity encouraged some to come forward who might not otherwise. Once the community saw what the tour was about, and that their identities (and the identities of the ghosts themselves) would be protected, more and more people were willing to share stories. Once I had opened the door to ghost stories, it seemed I became a magnet for them even outside the context of the tour. In my work at Heritage Saskatchewan, I travelled to dozens of Saskatchewan communities to offer workshops on intangible cultural heritage. After almost every workshop, at least one person would approach me to share an experience with ghosts or the supernatural. I heard ghost stories, sightings of the Little People, otherworldly beings dwelling in dark forests, deep lakes, and even exposed prairie hilltops. As there are ethics around who “owns” community history, so too there are ethics around how to deal with the question of belief. As I went into my work as a heritage practitioner, I was cautious about belief. Two incidents during my academic years made an impression on me when it comes to this issue. The first occurred in a history course on health and medicine when we came to the topic of what’s known in folklore as the Old Hag, more secularly known as sleep paralysis, which has different iterations around the world. After discussing how this phenomenon was experienced and perceived in previous centuries, the professor made a dismissive comment about how, of course these experiences can be scientifically explained now, effectively revealing her lack of belief. I interpreted this to mean that academic research and the supernatural were diametrically opposed. Then, a few years later in my graduate studies, I attended a reading from the author of a book about fairy lore in Newfoundland. Afterwards, I asked her about her research something in the way I was wording my questions must have implied an assumption that she didn’t believe in them. She stopped me and said, “I don’t not believe in them.” Her book was written with academic rigour and she managed to keep her person beliefs out of it, so I was surprised by her admission. As I have considered these incidents in the years since, I wonder if part of the history professor’s dismissal was her distance from the subjects, as it were, the people who experienced sleep paralysis in the sources she was using. Whereas the folklorist interviewed her subjects directly, heard them relate their experiences in their own words from their own mouths. It is harder to dismiss such stories as mere fantasy when you hear them over and over. If you work in community, and in heritage, you too might find yourself the recipient of stories of the supernatural. Whether you use these stories to talk about the heritage of your community or not, there is still a responsibility to honour the exchange. When you are taken into a person’s confidence as they tell a ghost story, you must consider how to receive it in an ethical and honourable way, no matter what your personal beliefs are. This can take some practice - to encourage the teller, to let them know you believe their experience without necessarily divulging your own belief or non-belief. Because it’s not about you, the recipient of the story. It’s about the community to which the teller, and perhaps you, belong. To believe or not to believe is not really the question when it comes to heritage practice and the subject of ghosts, ghouls, and other supernatural entities. I believe that belief needs to be besides the point. Belief is very personal, like religious and/or spiritual faith, and heritage practice is generally meant to be for community, and therefore needs to be as neutral on the question as possible. In my haunted history tour, I left the question of belief open to the participants to grapple with, using the line, “every single one of these stories I’m telling you really happened to someone in this community. Whether it was the supernatural or something else is up for you to decide.” The point is not about whether ghosts are real or not. For heritage practitioner and researchers, the point, in my view, is that talking about ghosts is a way to connect to the human history of a particular place. To talk about ghosts requires some context, and that context is history. The act of telling their story in the present is how it becomes heritage. Ghost stories are told and retold - passed from person to person. In their retelling they acquire a patina of sorts, as buildings do. In the case of stories, these are the small embellishments and details added or left out are usually retold in a way that makes the story, or the ghost, relevant to us now. In essence, ghost stories humanize history. They go hand in hand with old buildings - their spectral forms populating the empty rooms of heritage sites. The idea that what was once can endure still. And the knowledge that the lives we are living will one day be history, too. From David: “The present may not be as stable as we’d like it to be, and ghosts are frequently escaping the past. The question for us is, are we open to hearing them, and how will we respond?” In my hometown, there were some last ditch efforts to save the hospital before it was torn down. There was no way to save the hotel, despite the valiant efforts of firefighters, from its shocking loss in the middle of the night. Both buildings, once gone, left scars in the community for months afterward, as a demolition site and a smouldering ruin, respectively. Their losses caused many ghosts to spill out - as people grieved the buildings, like we grieve people, they shared memories, told stories about these places. And as for the reputed ghosts? I have heard that some of the ghosts of the old hospital have showed up in the new one - whether they followed familiar staff or residents of the care home, or the energy of the place, who can know? As for the hotel, I don’t know if its ghosts, like those of the ghost town, are displaced and yet still there, wandering the empty lot that was once their spectral home. What I do know is that their stories, now told and retold in the community, and therefore their lives, live on in people’s memories, continually resurrected in their retelling. Kristin Catherwood Mantta is a folklorist living in Moose Jaw. She worked for Heritage Saskatchewan from 2015-2024 and is currently on maternity leave from Parks Canada. Cover photo credit: Tourism RadvilleHaunted history

Photo credit: Patricia Verhelst

Mantta, giving a ghost tour in 2014.

Photo credit: Allison Fizzard

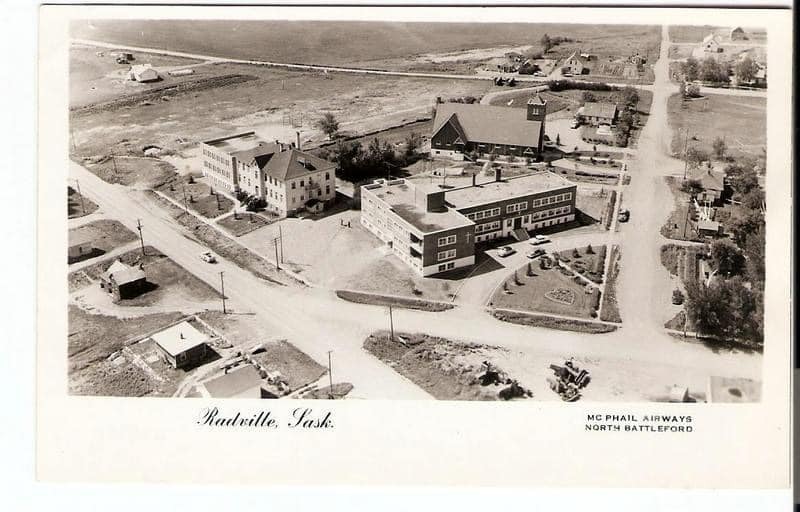

Photo credit: Tourism Radville

the smoking ruins of the historic Radville hotel.

Photo credit: Tourism Radville